This is the “engine” of learning. We just calculated the Loss (L). Now we need to know: “How much did each weight contribute to this error?”

If we know that increasing weight w11 by a tiny bit increases the error, then we should decrease w11. This “sensitivity” is called a Gradient.

We calculate these gradients using the Chain Rule of calculus, propagating the error backward from the output to the input.

dxdz=dydz⋅dxdy

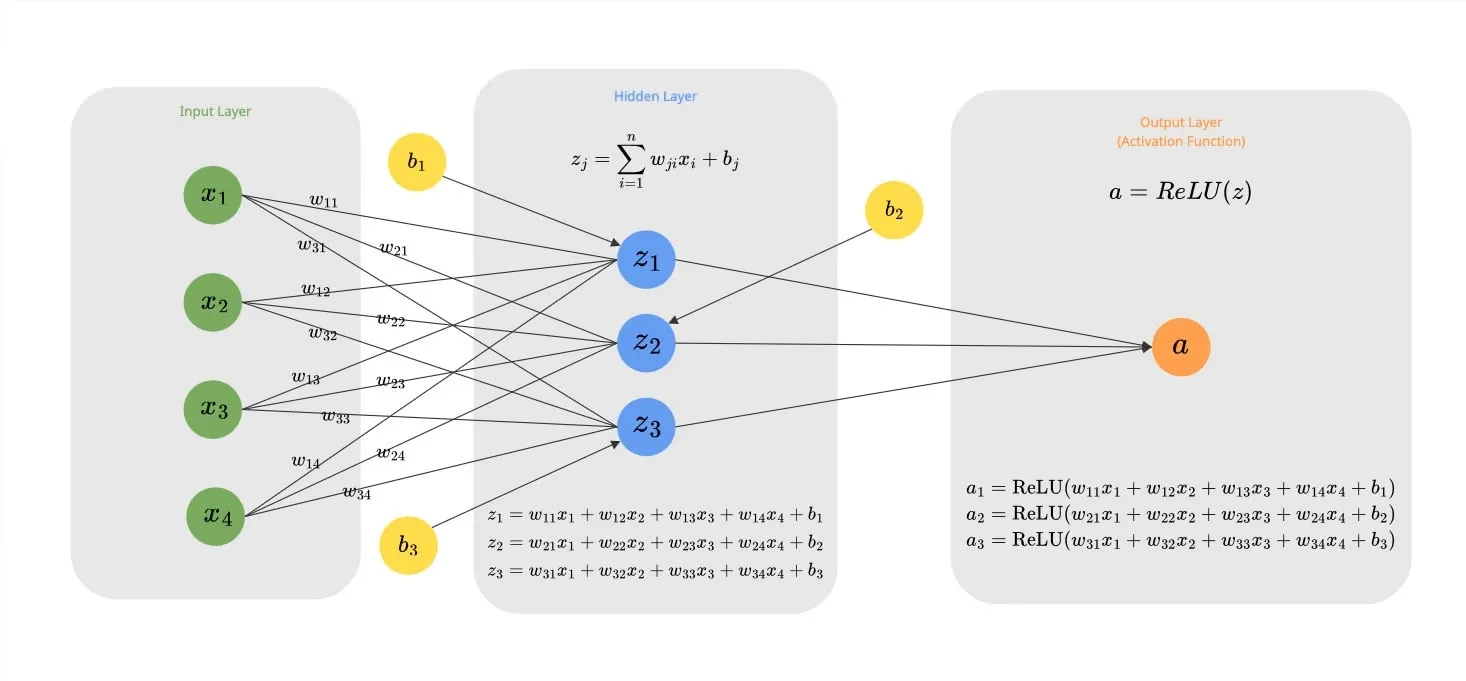

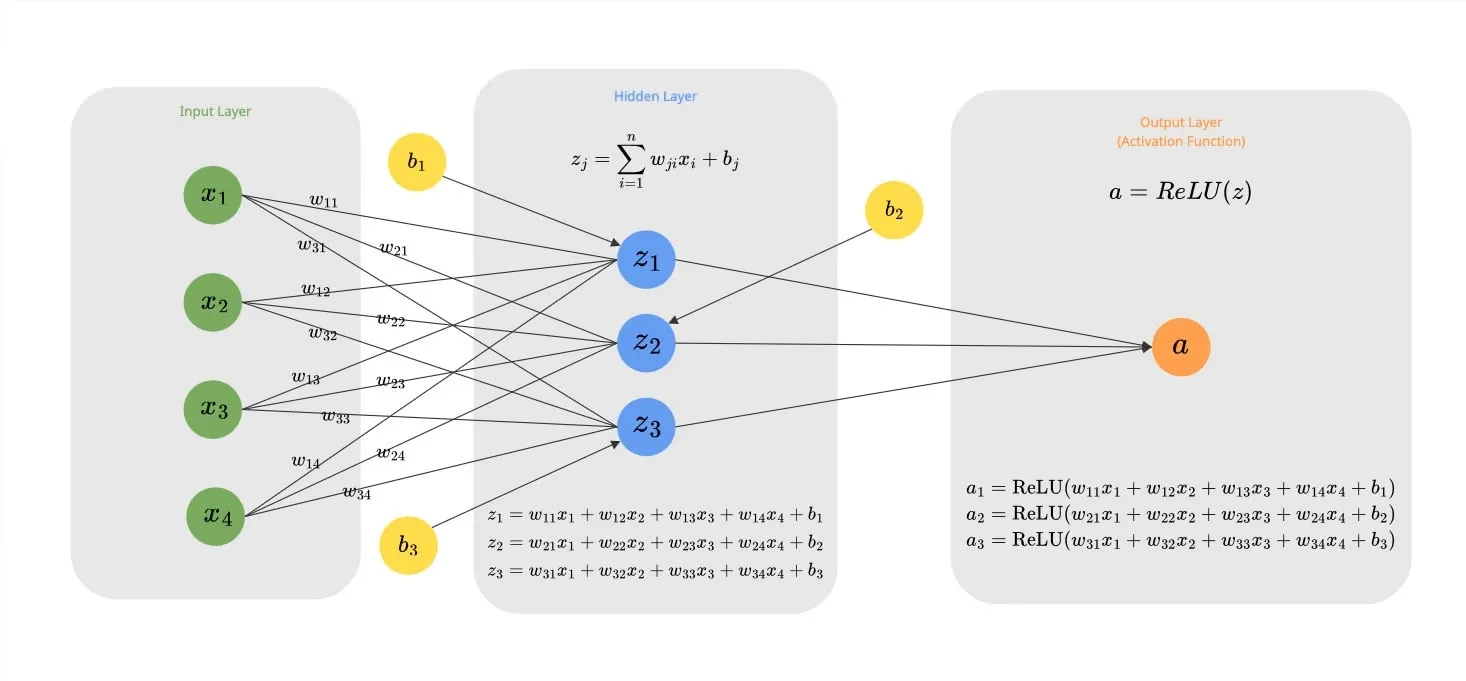

Let’s look at the simple network example that we saw above:

First, let’s calculate the loss function for the output a:

L=(a−Target)2=(ReLU(z)−0)2=(ReLU(sum(mul(x1,w1),mul(x2,w2),mul(x3,w3),mul(x4,w4),b)))2

(Note: In this specific example, we set the Target to 0 to simplify the math. We want the neuron to learn to output 0.)

To find the gradient of the Loss with respect to a specific weight (e.g., w11 connecting Input 1 to Neuron 1), we use the chain rule. We trace the path from the Loss back to the weight:

Path: Loss → ReLU → Sum → Mul → w11

∂w11∂Loss=∂ReLU∂Loss⋅∂sum∂ReLU⋅∂mul∂sum⋅∂w11∂mul

Using the values from our actual code execution (where x1=1.0, z≈0.964, a≈0.964):

- ∂ReLU∂Loss: The derivative of Mean Squared Error (n1∑(a−y)2) with respect to a. Since we have n=3 neurons:

- Formula: 32(a−Target)

- Result: 32(0.964−0)≈0.642

- ∂sum∂ReLU: Since z(0.964)>0, the slope is 1.

- ∂mul∂sum: 1.

- ∂w11∂mul: Input x1=1.0.

Final Gradient for w11:

∂w11∂Loss=0.642⋅1⋅1⋅1.0=0.642

This positive gradient tells us that increasing w11 will increase the error, so we should decrease it.